The Lost Ten Tribes of Israel, Part 2: How Were They Lost?

By JK Sellers

April, 24, 2025

- Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Assyria, Lords of War and Terror

- The Wickedness That Led to Captivity

- The Divided Kingdom: A Recipe for Trouble

- Idolatry: Bowing to False Gods at High Places

- Rejecting God’s Law: A Covenant Shattered

- Horrific Sins: Child Sacrifice, Witchcraft, and High Place Abominations

- Assyria’s Conquest of Israel and the Fall of an Empire

- Assyrian Deportation and Resettlement

- The Assyrian Exile

- The Regions of Exile

- A Divine Warning and Historical Reality

- The Fate of Israel’s Lost Tribes

- Conclusion: A Scattering with a Promise

- Notes

Introduction:

Few stories grip me like the mystery of the Lost Ten Tribes of Israel, their fate a puzzle woven from scripture, history, and whispers in prophecy. In Part 1, we followed their journey from Abraham’s covenant with God to the fracturing of Israel into two kingdoms, one fated to crumble under Assyria’s wrath. But how does a nation, chosen by God, vanish into the mists of time? The question burns with the weight of divine promise that still echoes today.

The story of their loss is no mere footnote; it’s a tale of rebellion, conquest, and a scattering that reshaped the house of Israel. From the Northern Kingdom’s defiance to Assyria’s brutal deportations, Part 2 dives into the crucible of 722 BC, when the Ten Tribes were carried away, their identity seemingly erased. Yet, even in their exile, whispers of hope and divine purpose linger, pointing to a future restoration that stirs the heart. Let’s step into this mystery together, piecing together how the tribes were lost and what their story means for us today.

Assyria, Lords of War and Terror

Ever since I was a kid, poring over Bible stories and ancient maps, I’ve been gripped by the raw power of empires that shaped the world through sheer force. Assyria is one of those juggernauts that stormed out of Mesopotamia in the 9th century BC and became the dominant political power in the Near East. Among the many conquered nations was the Northern Kingdom of Israel, the Ten Tribes were swept into oblivion, leaving behind a mystery that still haunts scholars and dreamers alike.

2.jpg)

Assyrian capital of Nineveh by James Fergusson (1808-1886)

Assyria, named for their chief god Ashur, sat in the heart of the Mesopotamian plain—modern-day Iraq, mostly. Hemmed in by the Syrian desert to the west, Babylonia to the south, and the rugged Persian and Urartian hills to the north and east, it was a land that bred warriors. The Subareans were likely the first to settle there, joined later by Sumerians, and by the third millennium BC, Semites rolled in, blending languages and arts with their neighbors. But unlike the softer Babylonians, the Assyrians had no time for luxury. They were a people carved from hardship—tall, bearded, and fierce, their monuments showing them striding over the Near East with iron resolve. Their story is one of kings and captives, of bloody triumphs and sudden collapses.

Map of the Farthest Extent of the Assyrian Empire.

Assyria’s rise to power came from a line of ruthless kings who stretched their borders and bent other nations to their will. It started with Shamshi-Adad (1813–1781 BC), who carved out Assyria’s independence. Later came heavyweights like Tiglath-Pileser I (1115–1077 BC), Ashurnasirpal II (883–859 BC), Shalmaneser III (858–824 BC), and Tiglath-Pileser III (744–727 BC), all the way to Ashurbanipal (668–627 BC). At their peak, these rulers forged an empire that dwarfed its rivals, swallowing Babylonia, Armenia, Media, Judea, Syria, Phoenicia, Sumeria, Elam, and even Egypt. It was a machine of control, unmatched in the Near East until Persia and Alexander came along, rivaled only by the likes of Hammurabi of Babylon or Egypt’s Thutmose III.

Assyrian Siege by Angus McBride

The heart of Assyria’s power was its army, a marvel of discipline and innovation. War wasn’t just a craft to them—it was a science. They honed infantry, chariots, and cavalry (pioneered by Ashurnasirpal), arming them with iron armor that gleamed in the desert sun. Siege engines, battering rams, and sappers who tunneled under walls gave them an edge over fortified cities. Their generals mastered strategy, outsmarting foes with brutal efficiency. But what made Assyria’s enemies tremble wasn’t just their skill, it was their savagery.

The Assyrians didn’t just conquer; they terrorized. A defeated city was looted, burned, and stripped bare, its trees felled to leave a wasteland. Soldiers were paid in plunder and prizes for every head they severed, turning victories into blood-soaked spectacles. Captives faced grim fates: slaughtered en masse, enslaved, or worse. Nobles were tortured—hands, feet, ears, and noses hacked off, or they were flayed alive, roasted, or hurled from towers. Ashurnasirpal boasted of skinning rebel leaders and draping their hides over pillars, impaling others on stakes. Ashurbanipal gloated about burning 3,000 prisoners alive, ripping out tongues, and feeding corpses to wild beasts. One king ordered his triumphs carved into bricks: “My monuments are built from the bodies of the slain. I crush men and beasts.” Nineveh’s reliefs show the grim reality—men impaled, skinned, or blinded, one king piercing prisoners’ eyes while tethering them by cords through their lips. It was no wondered that the prophet Jonah fled rather than go to the city of Nineveh to prophesy against it (Jonah 1:2).

This wasn’t just barbarism; it was a message. Assyria ruled by fear, ensuring no one dared to revolt. Yet, for all their might, their empire was fragile. A people who lives by the sword often die by it, and Assyria’s endless wars and cruelty sowed the seeds of their downfall.

What strikes me about the Assyrians is how their story echoes through time. They remind us of what happens when power forgets mercy, when conquest becomes an end in itself. The Ten Tribes of Israel vanished under their heel, scattered to the winds, but Assyria’s own end wasn’t far off. Like so many empires, they burned bright and brutal, only to fade into the dust of history.

The Wickedness That Led to the Assyrian Captivity of the Northern Ten Tribes

The Divided Kingdom: A Recipe for Trouble

If you’ve read my earlier piece on the Lost Ten Tribes, you’ll recall how the kingdom of Israel split after Solomon’s reign. His son Rehoboam’s stubborn refusal to ease the burdens on the people handed Jeroboam, a bold leader, the chance to take over the leadership of ten tribes—Reuben, Asher, Ephraim, Dan, Issachar, Manasseh, Naphtali, Zebulun, Gad, and the half-tribe of Manasseh (Machir)—into a new northern kingdom, called Israel. Judah and Benjamin, along with some Levites, stayed in the south as the kingdom of Judah. This division, around 931 BC, wasn’t just political; it set the northern tribes on a spiritual collision course.

Jeroboam and the worship of the golden calf, by Hans Collaert.

The Bible tells us in 1 Kings 12:26-33 that Jeroboam, fearing his people would return to Judah to worship at the temple in Jerusalem, made a fateful choice. He set up two golden calves—one in Bethel, one in Dan—and told the people, “Here are your gods, Israel, who brought you up out of Egypt.” Sound familiar? It’s a chilling echo of the golden calf at Sinai (Ex. 32), and it marked the beginning of the northern kingdom’s slide into idolatry. Jeroboam even appointed priests who weren’t Levites, breaking God’s commands about the priesthood (https://www.biblestudytools.com/1-kings/13-33.html). This wasn’t just a misstep; it was a deliberate rejection of the covenant God made with Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, and Moses.

Idolatry: Bowing to False Gods at High Places

The northern tribes didn’t just stumble into idolatry with Jeroboam’s golden calves; they ran headlong into it. In 2 Kings 17:7-17, the Bible paints a dark portrait of a people who “worshipped other gods and adopted the customs of the nations the Lord had driven out before them.” They built high places, pagan shrines dotting every hill and under every green tree, where they offered sacrifices to gods like Baal, Asherah, Molech, and Chemosh (2 Kings 17:9-11). These weren’t mere statues; they were a slap in the face to the God who split the Red Sea and gave them Canaan as an everlasting inheritance. At these high places, the Israelites burned incense, held wild festivals, and even engaged in cult prostitution and self-mutilation, practices borrowed from the Canaanites and condemned by God (Lev. 19:28).1

Hosea, preaching to these wayward tribes, called their idolatry spiritual adultery. In Hos. 4:12-13, he grieves, “My people consult a wooden idol… they sacrifice on the mountaintops and burn offerings on the hills.” Research shows these high places were more than altars; they were centers of debauchery where priests of Baal slashed themselves with swords and worshippers of Asherah joined in fertility rites with temple prostitutes to ensure bountiful crops.2 It’s heartbreaking to think Israel traded the living God for lifeless idols and shameful rituals, drifting further from the covenant that promised blessings for obedience (Deut. 29 and 30). This wasn’t a one-time lapse; it became their way of life, a generational betrayal that not only broke God’s covenants but His heart also.

Rejecting God’s Law: A Covenant Shattered

God’s covenant with Israel wasn’t just about worshipping other gods; it was about living as His holy nation, set apart by righteousness. But the northern tribes “rejected his decrees and the covenant he had made with their ancestors,” as 2 Kings 17:15 declares. They tossed aside the Law of Moses, ignored the Ten Commandments, and forgot the statutes that made them God’s treasured possession. 2 Kings 18:12 puts it bluntly: they “did not obey the voice of the Lord their God but violated his covenant.” This wasn’t just skipping a temple service; it was abandoning the very principles that defined them as God’s people, a choice echoed in their corrupt practices at the high places.

The prophet Amos saw this rejection in their daily lives and didn’t hold back. In Amos 2:6-7, he accuses Israel of “selling the righteous for silver and the poor for a pair of sandals,” crushing the needy while living in luxury. Research confirms this social injustice was rampant, with the wealthy exploiting the poor to fund lavish lifestyles, often linked to the festivals at high places where moral decay thrived.3 It’s a stark reminder that breaking the covenant wasn’t only about idol worship—it was about failing to love their neighbors, a sin that God, who demands justice and mercy, couldn’t overlook.

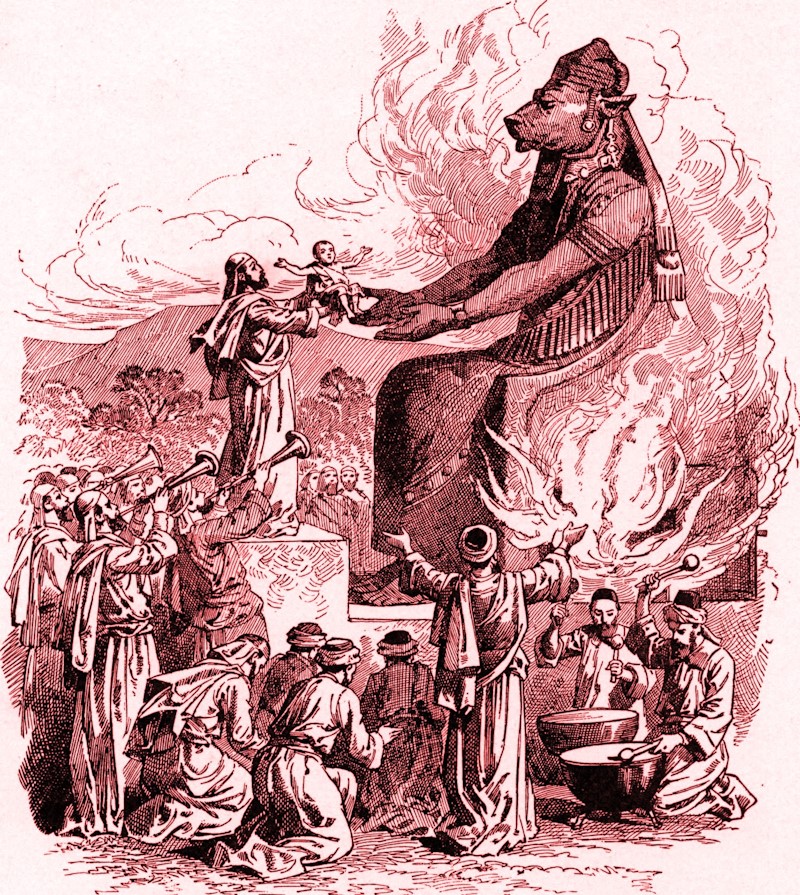

Child Sacrifice, Illustration from the 1897 “Bible Pictures and What They Teach Us.”

Horrific Sins: Child Sacrifice, Witchcraft, and High Place Abominations

If idolatry and injustice weren’t enough, the northern tribes plunged into sins that chill the soul. 2 Kings 17:17 reveals they “sacrificed their sons and daughters in the fire” and “practiced divination and sought omens.” Child sacrifice, often tied to Molech and Chemosh worship at high places, was a gruesome act God had explicitly forbidden (Lev. 18:21). Research highlights the horror: children were burned as offerings, sometimes thrown into fiery pits, to appease these false gods, a practice that profaned the sanctity of life.3 Yet, Israel embraced it, desperate for favor from idols.

They also turned to witchcraft, consulting mediums and soothsayers, often at these same high places, seeking answers from dark forces instead of the Lord (Deut. 18:10-12). The Bible says they “provoked the Lord to anger” (2 Kings 17:11), and it’s no wonder, research notes that high place worship included not just occult practices but also cult prostitution and self-mutilation, where devotees cut themselves in frenzied rituals to honor Baal (1 Kings 14:23).4 These weren’t just sins; they were a deliberate rebellion against the God who called them His own, a betrayal that sealed their fate.

Assyria’s Conquest of Israel and the Fall of an Empire

The fall of the Northern Kingdom of Israel to Assyria in 722 BC was a tragedy foretold by prophets, sealed by rebellion, and swallowed by the terror of an unstoppable foe. Assyria didn’t just conquer Israel; they erased it, scattering the Ten Tribes into the mists of history.

The prophet Isaiah warned Israel that if they didn’t turn back to God, Assyria would be “the rod of mine anger” (Isaiah 10:5). At the height of its power, Assyria was a name that chilled hearts, a war machine cloaked in tales of brutality. You’d think that reputation alone would’ve shaken Israel awake, but they ignored the warnings. Under Tiglath-Pileser II, Assyria tightened its grip on the west. By 738 BC, he was squeezing tribute from Damascus, Syria’s capital, and Samaria, Israel’s stronghold (2 Kings 15:19–20). Four years later, when both rebelled, Tiglath-Pileser crushed them. Damascus fell, parts of Israel’s territory were seized, and its people were dragged into captivity (2 Kings 15:29).

Tiglath-Pileser pioneered a grim tactic: mass deportation. By uprooting entire populations and scattering them across foreign lands, he aimed to shatter their unity and erase their identity.5 It was a cold, calculated way to break a nation’s soul. His successors, Shalmaneser V and Sargon II, continued the practice. When Israel’s king Hoshea revolted, Shalmaneser besieged the capital, Samaria, for three grueling years. He died before the city fell, but Sargon II finished the job, razing Samaria and dragging the survivors into Assyria (https://www.biblestudytools.com/2-kings/passage/?q=2+kings+17:1-6). With that, the Northern Kingdom vanished from the pages of the Old Testament, and the Ten Tribes became a lingering mystery.

Assyria’s shadow soon loomed over the Southern Kingdom of Judah. Sennacherib, Sargon’s heir, rampaged through Judah during King Hezekiah’s reign, leveling its major cities. But Jerusalem held firm, spared by divine intervention (2 Kings 19:35). Thwarted, Sennacherib slunk back to Nineveh, Assyria’s glittering capital.

Nineveh, where Jonah once preached repentance, was Assyria’s final stronghold, rebuilt by Sennacherib with mighty walls and a canal to quench its thirst. Yet prophets like Zephaniah and Nahum foresaw its doom (Zeph. 2:13–15; Nahum 3). In 612 BC, their words came true when Nineveh fell. Assyria itself unraveled, undone by its own success. As historian Will Durant put it, the empire’s victories bled it dry.6 The bravest died in battle, leaving the weak to multiply. Endless conquests drained the land and flooded Assyria with captives—millions of desperate souls who bred unrest and fractured the nation’s core. The army, once a juggernaut, filled with foreign conscripts, while raiders chipped away at overstretched borders.

The end came swiftly. In 625 BC, Nabopolassar’s Chaldeans and Babylonians drove Assyria out of Babylonia. Two years later, the Medes and Babylonians took Ashur. By 612 BC, Nineveh collapsed, and with it, Assyria’s empire. Babylon rose as the new terror of the Near East, claiming the fear and tribute Assyria once demanded.

What gets me about this story is its stark lesson: no empire, no matter how fierce, is eternal. Assyria’s rod of anger broke Israel, but it also broke itself. The Ten Tribes were lost, scattered to the winds, but Assyria’s own pride and cruelty paved the way for Babylon’s triumph. It’s a reminder that power, unchecked, consumes its wielder as surely as its victims.

Assyrian Deportation and Resettlement

When I read about Assyria’s conquest of the Northern Kingdom in 722 BC, I can almost hear the cries of families torn from their homes in Samaria, marched to far-off lands like Halah, Habor, and the cities of the Medes (2 Kings 17:6). Starting with Tiglath-Pileser III’s invasions around 732 BC, and sealed by Sargon II’s siege of Samaria, tens of thousands—maybe 40,000 by some counts, were dragged into exile, their identity meant to dissolve in Assyria’s vast empire. The Assyrians didn’t stop at exile; they brought in foreigners from Babylon, Cuthah, Avva, Hamath, and Sepharvaim to settle the land (2 Kings 17:24). These foreigners rebuilt Samaria’s towns, tilled its fields, and brought their idols, reshaping a land God gave to His covenant people. It’s a chilling picture of judgment, a nation lost not just to war but to a deliberate erasing of who they were meant to be.

Jesus and the Samaritan Woman at the Well

Those foreigners mingled with the few surviving Israelites left behind, and from that mix came the Samaritans, a people who’d spark centuries of bad blood with the Jews. The Jews despised them, and it’s not hard to see why, Samaritans were seen as half-breeds, their blood and faith tainted by pagan roots (2 Kings 17:29-31). They followed a faith that looked Jewish but wasn’t, praying to God yet honoring Mount Gerizim over Jerusalem’s temple and blending pagan practices that echoed their ancestors’ false gods. To the Jews, this was a betrayal of the covenant, a mockery of the temple and the pure worship God demanded (John 4:20-22). They shunned Samaritans, treated them like outcasts, and by the time of Christ, the divide was so bitter a Jew wouldn’t even walk through their land (John 4:9). Yet, Jesus chose a Samaritan woman at the well to first hear Him declare, “I, the one speaking to you—I am he (the Messiah).” showing salvation was for all who’d listen (John 4:25-26). It’s a sobering lesson: Israel’s sin didn’t just scatter the tribes; it birthed a rift that turned God’s people against each other. Still, I’m struck by God’s mercy, through Jesus’ encounter with the woman at the well and the parable of the Good Samaritan, He showed even those despised could receive His love.

Relief Sculptures on the Temple Wall of Nineveh Showing the Battle of Lachish. Captives being led away.

The Assyrian Exile

When Tiglath-Pileser III and later Assyrian rulers swept through Israel around 732–722 BC, they didn’t just conquer cities and slay tens of thousands—they uprooted thousands of the surviving Israelites, scattering them across the Assyrian Empire. The Bible tells us exactly where these captives ended up, and history backs it up. Let’s follow their trail to places like Halah, Habor, the cities of the Medes, and Kir, and see what this exile meant for God’s people.

The Regions of Exile

Picture this: families torn from their homes in Galilee and Samaria, marched hundreds of miles to strange lands. The Bible, in 2 Kings 17:6, lists their destinations: “Halah, Habor by the river of Gozan, and the cities of the Medes.” Halah was likely a rugged spot in northern Mesopotamia, maybe near the Tigris River in what’s now Iraq.7 Habor, by the river Gozan, points to the Khabur River in northeastern Syria, a fertile area where the Assyrians parked their captives to work the land or build their cities.8 The cities of the Medes? That’s way out east, in modern northwestern Iran, a distant corner of the empire where Israelites were sent to fade into the Assyrian machine.9 Some, especially from earlier campaigns under Tiglath-Pileser III, ended up in Kir, possibly in southern Mesopotamia or near Elam, as 2 Kings 16:9 hints.10 Reading this, I can feel the weight of their loss—God’s people, scattered into the wind, far from the land promised to Abraham.

A Divine Warning and Historical Reality

This wasn’t just Assyrian politics at work; the Bible frames it as God’s judgment for Israel’s sins—idolatry, child sacrifice, and those shameful high place rituals we’ve talked about (2 Kings 17:7-17). God had warned them through prophets like Hosea and Amos: turn back or lose everything (Hosea 4:12; Amos 5:11-12). When they didn’t listen, God used Assyria as His “rod of anger” (Isaiah 10:5). Assyrian records, like Sargon II’s boast of deporting 27,290 from Samaria, match the Bible’s story, showing captives were sent to places like Gozan and Media to labor or assimilate.11 Archaeological finds, like the Nimrud tablets, confirm these regions as resettlement hubs.12 For me, it’s a gut-punch reminder: God keeps His promises, blessings and curses alike. The Israelites’ exile to Halah, Habor, Media, Kir, etc. wasn’t just a tragedy—it was a call to remember who they were meant to be.

The Fate of Israel’s Lost Tribes

After the northern kingdom of Israel fell to the Assyrians around 722 BC, you’d think every last soul from those ten tribes was gone, scattered to places like Halah and Habor. But 2 Chron. 30 tells a different tale. King Hezekiah, the righteous ruler of Judah, reached out to the remnant of Israel who hadn’t been exiled, inviting them to celebrate Passover in Jerusalem. It’s a story of second chances, stubborn hearts, and a few humble souls who answered the call. Let’s dive into this moment, where God’s grace met a broken people, and see what it means for us today.

Hezekiah’s Invitation and the Remnant’s Response

King Hezekiah wasn’t content to let the northern tribes fade into oblivion after Assyria’s conquest. Around 715 BC, he sent messengers across Judah and Israel, from Beer-sheba to Dan, with a heartfelt plea: come to Jerusalem to keep the Passover, a feast to honor the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob (2 Chron. 30:1, 5). The Bible says he wrote letters specifically to Ephraim and Manasseh, urging, “Ye children of Israel, turn back unto the LORD… that He may return to the remnant that are escaped out of the hand of the kings of Assyria” (2 Chron. 30:6) He warned them not to be “stiffnecked” like their ancestors, who’d provoked God’s wrath, but to serve the Lord so His “fierce anger may turn away” (2 Chron. 30:8). When those messengers hit the roads of Ephraim, Manasseh, and Zebulun, they got more jeers than cheers—people laughed and mocked them (2 Chron. 30:10). Yet, a spark of hope flickered: some from Asher, Manasseh, and Zebulun humbled themselves and headed to Jerusalem (2 Chron. 30:11). I can’t help but admire their courage to stand out in a crowd of scoffers.

.jpg)

King Josiah cleansing the land of idols by Hole, William Brassey ( 1846-1917)

A Joyful Passover and a Cleansing of the Land

This Passover, delayed a month to make room for all comers (2 Chron. 30:2), was unlike any since Solomon’s day. People from Judah, joined by a multitude from Ephraim, Manasseh, Issachar, and Zebulun, plus strangers (proselytes who had embraced Judaism and been circumcised) from the land of Israel, gathered in Jerusalem (2 Chron. 30:18, 25). Even those who hadn’t purified themselves ate the Passover, covered by Hezekiah’s prayer: “The good LORD pardon” (2 Chronicles 30:18). The Bible says, “There was great joy in Jerusalem; for since the time of Solomon… there was not the like in Jerusalem” (2 Chronicles 30:26). Scholars like Umberto Cassuto and Elia Samuele Artom suggest Hezekiah may have even annexed parts of Ephraim and Manasseh, where these remnant Israelites lived, bringing them under Judah’s wing (2 Chronicles 30). After the feast, the fire of revival spread. The remnant, along with Judah’s people, marched out and smashed the idols—Baal’s pillars, Asherah poles, and high places—across Judah, Benjamin, Ephraim, and Manasseh, wiping out every trace of false gods (2 Chron. 31:1). Reading this, I’m struck by the power of a remnant choosing God over idols, a reminder that it’s never too late to turn back.

A Lesson for Us All

The northern tribes had strayed far, worshipping false gods and breaking God’s covenant, yet a remnant remained, and God hadn’t given up on them. Hezekiah’s call echoes God’s mercy: “For if ye turn back unto the LORD… He will not turn away His face from you” (2 Chron. 30:9). Some mocked the invitation, but those from Asher, Manasseh, Zebulun, and Issachar who showed up found joy and purpose, sparking a cleansing of the land. It makes me wonder: what “high places” in our own lives need tearing down? Like those remnant Israelites, we all get second chances to return to God, to choose joy over scorn. Their story, preserved in 2 Chronicles, is a beacon of hope, showing that even in the shadow of exile, God’s grace is bigger than our failures.

Conclusion: A Scattering with a Promise

The fall of the northern kingdom of Israel in 722 BC is a heart-wrenching chapter in the Bible, a story of a chosen people lost to the winds of Assyria’s wrath. Their idolatry, injustice, and horrific sins at high places broke the covenant with God, inviting His judgment through Tiglath-Pileser III, Shalmaneser V, and Sargon II (2 Kings 17:6-17). Yet, even as they were marched to Halah, Habor, and the cities of the Medes, a flicker of hope remained. Hezekiah’s Passover showed us a remnant who clung to God, smashing idols and choosing faith (2 Chron. 30:11, 31:1). It’s a reminder that God’s promises to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob—to make their descendants a great nation—don’t fade, even in exile (Gen. 17:4-7). The Ten Tribes may seem lost, but the Bible hints at a future gathering, a restoration that stirs my soul (Isaiah 11:11-12). Their story challenges us to hold fast to God’s covenants, knowing His mercy outlasts our failures.

Where did the Lost Ten Tribes wander after their Assyrian exile? Could they have reached distant lands like India, Ethiopia, or even Japan, carrying fragments of their covenant? In Part 3, we’ll explore the tantalizing clues—biblical, historical, and legendary—that trace their paths across the globe. Don’t miss the next chapter of this divine mystery!

Notes:

- The Battle of the Gods: Paganism’s Seduction of Israel – Israel My Glory

- What Are the “High Places” in the Old Testament? - Eternal Perspective Ministries

- The Pagan Gods of the Old Testament - Bezalel Messianic Fellowship

- Cutting, McClintock and Strong Biblical Cyclopedia

- The Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible, s.v. “Assyria and Babylonia,” 1:272

- Will Durant, Our Oriental Heritage, The Story of Civilization, 1:283.

- Topical Bible: Halah

- Assyrian empire builders - Israel, the 'House of Omri'

- Tiglath Pileser III - World History Encyclopedia

- Tiglath-Pileser of Assyria invades Israel - The Bible Journey

- Tiglath-pileser III’s Attack on Israel Confirmed | adefenceofthebible.com

- Tiglath-Pileser III - New World Encyclopedia

See Also:

The Lost Ten Tribes of Israel, Part 1: Who Are They? Explore Part 1 as I delve into the mystery of the Lost Ten Tribes of Israel. Trace their origins from Abraham to the Divided Kingdom in this captivating historical journey.

Gods and Goddesses, Pagan: Baker's Evangelical Dictionary of Biblical Theology

What Do We Know about the Lost Tribes of Israel? By Betty Dunn